Música de los Andes (2006)

Música de los Andes (Music of the Andes) is a work in five movements, each based on a particular musical genre of the peoples of the Andes mountain range in South America: huayno, bailecito, sanjuanito, danzante, and cueca boliviana. Composer Marcelo Coronel dedicated this work to guitarist Christopher Dorsey.

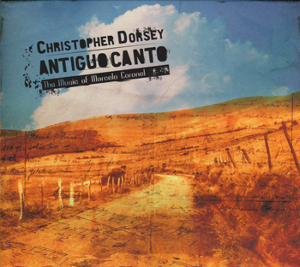

I. Antiguo canto (huayno)

“Antiguo canto” (Ancient song) is based on the huayno, a collective dance form found in the Andean region from Ecuador to the Argentine northwest. Examples of the huayno exist in song form typically accompanied by charango. As an instrumental genre, the huayno is often performed in religious processions by bands of sikus (pan flutes) and accompanied by el bombo (the bass drum) and other regional instruments. The source of the huayno is pre-Hispanic, before which its history and development escape further elucidation. The beat and meter type is simple duple, and the melody is characteristically pentatonic minor, or modal. “Antiguo canto” follows the Dorian and Aeolian modes. The atmosphere and the form of this music can show considerable variants. In the northern Andean region, it is festive and energetic, whereas in the Argentine northwest, the huayno has a slower tempo, especially in the work of current musicians. “Antiguo canto” corresponds with this latter type.

II. El viento blanco (bailecito)

“El viento blanco” (The white wind) is a bailecito, a characteristic and strongly rooted dance genre of the provinces of Salta and Jujuy in the Argentine northwest. In the mountainous areas of this region, winters are hard. Native inhabitants call low clouds comprising furious winds el viento blanco. These winds disperse the fallen snow into the air producing white-outs, causing those unfortunate ones trapped in the storm disorientation, hypothermia, sleep, and even death. In the story El viento blanco (1922), Argentine writer Juan Carlos Dávalos reported the vicissitudes of unfortunate muleteers surprised by this inclement natural phenomenon in the middle of the chain of mountains. The beat and meter type of the bailecito is compound duple, and typically in the minor mode. Argentine musicologists call the superimposition of 6/8 and 3/4 meters, common to so many South American musical genres, polirritmia (polyrhythm) or birritmia. This lively metrical style originated in the Spanish music of the Renaissance.

III. Inti Raymi (sanjuanito)

Inti Raymi (Festival of the Sun) is an indigenous Inca festival that is celebrated in Ecuador every June. Its characteristic homage to the harvest is manifested through singing, dancing, and other rituals. Hundreds of people come from diverse points of the country to take part in this happening. The people typically sing sanjuanitos, which is music of great vitality. However, the music’s origin is a source of controversy: for some it originates from pre-Hispanic Ecuador while others maintain that it comes from the Inca culture of Peru.

IV. Sasañán (aire de danzante)

Sasañán (Difficult path) is an expression taken from Quechua, a Native American language of South America. This difficult path has been the way of life for the marginalized Andean peoples throughout centuries and is still their lot in life-to be ignored, exploited, discriminated against, and deprived. To compose the piece, the composer has taken as a guide the atmosphere and general characteristics of the popular Ecuadorian “Vasija de barro” (Vessel of clay), a song which references the Inca tradition of burying the dead in a vasija de barro. “Sasañán” is of a sad, slow, but persistent tempo in a straightforward compound duple meter, characterized by a flowing melody based on the Dorian mode.

V. Cuequita (cueca boliviana)

The Bolivian cueca is a dance-one of the branches in which the Peruvian zamacueca bifurcated in its dispersion towards the south. This little cueca is characteristically fast and exemplifies the widespread South American use of the metrically ambiguous compound duple meter. Cuecas are popular not only in Bolivia, but also in the Argentine northwest.

Imaginario popular argentino: centro y noroeste (2000)

Composer Marcelo Coronel wrote Imaginario popular argentino: centro y noroeste (Popular argentine fantasy: central and northwest) after being invited to participate in a radio program dedicated to the folklore of South America. That program, which would address the myths, beliefs, superstitions, and legends of the subcontinent, inspired Coronel to conduct research on the subject. In that process, he discovered the diversity and richness of nuances that characterize the South American folklore.

Imaginario is a series of five pieces for guitar that highlights the folklore of central and northwest Argentina. Two of the works are named for deities: la Pachamama and la Coquena. One is a superstition, la salamanca, and another is phantasmagoric: la Umita. A very curious custom, el velorio del angelito (wake for the little angel), inspired the final piece. The form of each piece is based on a musical genre indigenous to the region influenced by the corresponding belief.

I. Pachamama (zamba sin segunda, a modo de preludio)

La Pachamama (Mother Earth) is the greatest divinity of the indigenous of Bolivia, Peru, and northwest Argentina. She is identified with the land and her temple is all of nature.

In her honor, travelers and locals create little mounds of stones arranged in a conical form that they raise on the edges of paths, especially in the summits. There they make requests of la Pachamama and leave offerings-a frayed piece of a poncho, some coca leaves, or a small amount of chicha (a popular Andean fermented beverage). She intervenes in all aspects of life, and the people ask her for blessings such as a successful sowing time, fertile livestock, protection from freezes and pests, for luck in the hunt, and the avoidance of mountain sickness while traveling. In some regions of Salta, they believe that la Pachamama is an old Indian woman who keeps vigil over all that live in the valleys and protects the treasures of the ancients.

The heritage of the zamba comes from the Peruvian zamacueca, which itself is derived from the eighteenth-century Spanish fandango. A couple’s dance, it is one of the most common song forms of Argentine folk music. The dance represents the man’s intention to gain the love of his partner; and the pañuelo (handkerchief, representing words unspoken), is an essential element of the dance that signals the sequences of the courtship. The mood of the zamba can vary in tempo and mood from fast and festive to slow and nostalgic. This piece is an example of the latter. Typically, the formal structure of a zamba is an introduction, followed by two estrofas, and then the estribillo before a da capo. “Pachamama” follows this form but does not feature a da capo-hence the subtitle sin segunda (without a second part).

II. Salamanca (chacarera)

La salamanca is the place consecrated to the cult of the devil, usually a pit or a distant cave in the forest. Pilgrims to the site ask for certain powers or abilities, such as playing musical instruments with an unequaled ability, singing marvelously, being irresistible in love, or (for those inclined to knife fights) to be invincible with a blade. Women who assemble there generally do so to learn witchcraft.

The devil teaches the women how to cause harm to others. However, reflecting the devil’s contract of the Faust legend, every mortal favored with such special talents is left with a compromised soul, and the devil would be the only owner who in due time would reclaim what is his. The magnetic, joyful music of la salamanca attracts those within its surroundings. Religious symbols at the shrine’s entrance must be renounced before entering. Once inside, the candidate must endure the siege of repulsive creatures-enormous toads, bats, and serpents-that surge forward upon him. If he is able to control himself, he suffers no harm, but if not, he will die. Next, he encounters a group of men and women dancing joyfully to the music of a harp, and a bruja (witch) invites him to the dance, which lasts the entire night. As dawn’s first rooster crows, the petitioner receives the supernatural power in exchange for his soul.

Formally, “Salamanca” is a chacarera, another couple’s dance. Originally from Santiago del Estero, it is a lively dance that has become very popular throughout Argentina. The formal structure of la chacarera simple is interludio, copla (or estrofa), interludio, copla, interludio, two coplas with a da capo. Besides the characteristic 6/8 polyrhythmic nature of the chacarera, an interesting harmonic element is the use of what Argentine musicologists refer to as la escala bimodal eólico-dórica-a hybrid scale of the Aeolian and Dorian modes, especially characteristic of compositions wherein the melody is harmonized in thirds.

III. Coquena (baguala)

In the Argentine provinces of Salta and Jujuy, there exists a magical creature called Coquena that is considered to be a guardian of vicuñas, llamas, and guanacos. Those who have seen him describe him as a dwarf with indigenous features, dressed as a shepherd. Coquena guards the livestock that graze in the hills and avoids contact with humans. Meeting him, an encounter that never lasts for more than an instant before he transforms into a spirit, is a bad omen. Animals wandering apparently independently are said to be herded by Coquena, who continually chews coca and whistles. During the night, he drives herds loaded with gold and silver to the Cerro Rico (Rich Mountain) of Potosí, Bolivia, so that its riches are never exhausted. It is said that he can be very generous with good shepherds, whom he rewards with gold coins. However, anyone who mistreats vicuñas and guanacos or overloads the llamas is severely punished. This belief has helped protect against the extinction of the animals necessary for food, clothing, and transport.

“Coquena” is a baguala, a vocal music genre of a pre-Hispanic source from the northwest region of Argentina. Of slow or moderate tempo, it is typically accompanied by a caja, a hand-held drum played with a mallet. Sometimes the baguala is sung as a solo in a rhythmically free manner. The melodic structure is based on a simple major triad.

IV. La Umita (vidala santiagueña)

In Santiago del Estero, Argentina, there is a legend of la Umita (the little head), a disembodied head with long, tangled hair, which customarily roams alone through the night, rolling upon the ground or flying at ground level and producing a smooth sound, similar to the rustling sound of a wheat field swayed in the wind.

La Umita might be the soul of a deceased person condemned to pay for a mistake or an error in life. Typically, la Umita appears in abandoned villages or old paths and implores travelers to help it escape its anguished situation. Unfortunately for la Umita, its appearance usually terrorizes travelers and provokes their flight. However, some do not fear la Umita-even those who endure its constant moans in return for driving away evil spirits while traveling at night. These travelers leave water in a remote place so it can drink. It is only thirst that brings la Umita from its refuge. La Umita rests at the break of dawn.

“La Umita” is a vidala santiagueña, a secular song form that has its roots in the province of Santiago del Estero. Etymologically, vidala incorporates the Spanish word vida (life) and the Quechua suffix “lla” that signifies “no more.” It is most commonly a slow song. The music of the vidala is typically bimodal-a fusion of the melodic minor scale and the major scale featuring a raised fourth degree to preserve parallel thirds. Other variants exhibit a minor tonality or occasionally, a major tonality.

V. Velando al angelito (gato)

People of Argentina’s interior, especially those in the north and the northwest, believe that children who die before the age of seven are pure beings, uncontaminated by the miseries of human nature. As such, they are considered little angels that go directly to heaven, as opposed to adults who must first endure Purgatory before entering into Heaven.

At the passing of a child, the parents observe el velorio del angelito (wake for the little angel), which is attended by relatives and neighbors. The godmother prepares the body of the child. On the ceiling of the room where the wake is held, she hangs a sheet that represents heaven. The little casket is placed on a table and is adorned with paper flowers. A string is tied to the little child’s waist, so that when the godmother dies and enters Purgatory, she can take hold of the string and ascend to heaven. Requests for favors are indicated by knots in a ribbon or string placed around the casket. Later, mourners gather for a dance. The reunion is brightened with drums, guitars, violins, and harps while coffee and drinks are passed around to revive the distressed spirit of the relatives and friends.

At midnight, the godmother begins the first dance, called el baile del angelito (dance of the little angel). She takes the casket in her arms and dances to the beat of the music. After a few minutes, she surrenders the little angel to the godfather, who finishes the farewell to the godchild between dance figures and zapateados (foot taps). At this moment, all those present devote themselves to dancing gatos and chacareras, singing, drinking, and celebrating the arrival of the little angel to heaven. Crying is not allowed in these gatherings because the tears soak the wings of the child, making it difficult to ascend to heaven. After returning from the burial, the guests are once again invited to enjoy little cakes and strong drinks. And as in all gatherings in which the guests have spent many hours consuming alcoholic beverages, excesses and fights are not uncommon.

In the year 1950, the government of the province of Santiago del Estero prohibited los velorios del angelito together with other popular fiestas of a pagan nature, hoping to regulate the religious life of the people in accordance with the dogmas of the Catholic Church. That probation notwithstanding, los velorios del angelito continue to be celebrated as before.

“Velando al angelito” is a gato, another couple dance, which is practiced in the central and northwest of Argentina. It is most often in a major tonality and may be instrumental or sung. The gato exhibits the polyrhythmic nature of many other South American dances in 6/8, and its formal structure is introduction, three short coplas, zapateo, copla, zapateo, copla, and da capo.

Temple del Diablo (2008)

Popular musicians from South America have often used alternate temples (tunings) of the guitar, in order to make the performance of certain keys more accessible. Composer Marcelo Coronel wrote Temple del Diablo (Tuning of the Devil) using one of those alternate tunings: fifth string in G and sixth string in D, keeping the remaining strings in accordance with the standard tuning. Over the years the composer had heard in a vague but recurrent way that this tuning is called temple del Diablo. In his attempts to find out the source of this designation, he found many different tunings covered by the same expression, including the one that is used for these compositions. So, rather than finding a categorical answer, he discovered a vast and confused phenomenon that still requires a thorough study. Coronel thus uses the temple del Diablo designation only generically here. Since the manifestations of folklore cover their sources with an unfathomable cloak of vagueness and forgetfulness, it is quite likely that the true story will never be known.

I. Preludio

As the title indicates, this piece is nothing more than a brief introduction to the series. “Preludio” (Prelude) is not based on a specific Argentine music genre.

II. Danza de las abejas (huayno)

Several years ago, a colony of bees settled in the hollow trunk of a massive old tree growing in front of the composer’s house. He saw the bees everyday from his window, flying in circles around the trunk and multiplying until finally, they became a real danger. Therefore, he began to observe them with the intention of finding a way of eradicating the colony, but ultimately came to admire this prodigious example of social organization in the service of the work.

Bee language indicating a new source of food attracted Coronel’s attention especially. In this event, the explorer bee returns to the colony and dances to show the others the distance and direction of the nectar’s source.

In those days, Coronel was composing this huayno and decided to title it “Danza de las abejas” (Dance of the bees) in memory of that colony that had been a part of his daily landscape.

III. Casi nada (chacarera)

In 2002, the broadcast "De Segovia a Yupanqui " (From Segovia to Yupanqui), created and conducted by Sebastián Domínguez, celebrated twenty years of uninterrupted broadcasts on Radio Nacional Argentina. Marcelo Coronel composed this chacarera, “Casi nada” (Almost nothing), as a way of celebrating such an important event for the guitar.

IV. Coral

In reality, Temple del Diablo was conceived and published in two parts. The second part begins with this brief chorale which presents a lower pedal on the fifth string of the guitar (tuned to G) and a succession of chords in three voices. The resulting harmonies form a rather “dark" world of sonorities.

V. Machetazo (gato)

An explorer opens a new path with his machete. Where there once was only impenetrable undergrowth emerges a path simultaneously discovered and traveled. Later, others will follow, consolidating and modifying this new route; each one will leave his footprints. Juan Falú gave a strong blow with a machete that opened the way for the renovation of Argentine music for guitar. “Machetazo” (With a big swing of the machete) is a lively gato¬ and is dedicated to Juan Falú. Though most gatos are in a major tonality, this gato is in the less common minor tonality.

VI. Andar y andar (vidala santiagueña)

Some men choose the destiny of traveling-they do it by conviction, by their own decision. Others, longing to find their place in this world, are forced to move from place to place as involuntary nomads. Darío Montiel is one of the latter-a restless soul. The composer met him in his brief stay in Rosario, and there they became friends. Montiel still travels from here to there, longing for the day when he can take root somewhere. “Andar y andar” (To walk and walk) is a slow, deliberate vidala santiagueña.

VII. Señor Guitarra (chaya)

Musical expressions of the people begin to transcend their regional area when a popular artist transports them, in minstrel-style peregrination, to other regions (cities, provinces, and even countries). Many times these spokesmen of the popular culture carry their treasure almost untouched, offering it intact to those inclined to listen. But from time to time a different artist arises-one who possesses a great sensibility and a more distant creative horizon. When this happens, the music evolves to a higher state and begins, from a native root, to become universal. Such is the case with the music of guitarist and composer Eduardo Falú, whose interpretations and compositions have underscored his noble presence, placing the Argentine guitar in a place of great prestige.

“Señor Guitarra” (Mr. Guitar-or perhaps more reverently Lord of the guitar) is a chaya or vidala chayera, a lyrical form from the vicinity of the Argentine province of La Rioja. It is related to the cueca by its rhythmic characteristic, fast movement, and joyful character. Chaya is also a large festival of joy and friendship that is celebrated in La Rioja each year in February during the time of carnaval (carnival).

Amazon

Amazon