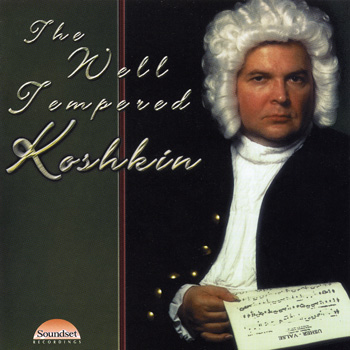

Composer-performers who write primarily for their own instruments plow furrows narrow but deep. Paganini pushed back the technical limits of the violin, gaining for the instrument a new range of musical possibilities. Chopin's music unleashed the expressive potential of the piano to the great profit of later composers. The ambition of the Russian composer-guitarist Nikita Koshkin in writing music for his instrument has been twofold: to expand the vocabulary of effects on the guitar; and, more importantly, to develop means to incorporate these into musical expressions. The works on this, Koshkin's first professional recording, accomplish both with high craftsmanship, passion and a typically Russian blend of fervor and pathos.

Born in Moscow in 1956, Koshkin recalls liking the music of Shostakovich and Stravinsky at age 4. His parents planned a diplomatic career for young Nikita, however, and until he was 14, rock was his only musical interest. That year, his grandfather gave him a guitar and a recording by Segovia, and his life was changed. Composing for and playing the guitar became his double passion, and he went on to study guitar with George Emanov at the Moscow College of Music, and with Alexander Frauchi at the Gnesin Institute (Russian Academy of Music), where he also studied composition with Victor Egorov. Koshkin's composing profile gained international stature in 1980, when Vladimir Mikulka premiered his suite for guitar, The Prince's Toys. Koshkin's music, which includes scores for guitar ensembles and works for guitar with other instruments and the voice, has since been performed by artists such as John Williams, the Assad Duo, and the Zagreb and Amsterdam Guitar Trios. Koshkin is also an active concertizer, with tours of Russia, Central and Western Europe, Great Britain and the United States to his credit. This recording was made in Arizona, while he was in the United States in 1997 as a featured artist of the Guitar Foundation of America International Convention in southern California.

Koshkin calls Prelude and Waltz: Homage to Segovia 'a light remembrance' of the master whose recording turned the young Koshkin from rock music to the classical guitar. Written in the year of Segovia's death (1987), the two-movement form derives from early examples of paired movements, especially pavanne-galliard, though prelude and waltz are nowhere else mated in any repertoire known to this writer. The brooding prelude leads easily to the whimsical waltz by way of motific relationship: the theme of the waltz mirrors the prelude's five-note motto. Guitar was the result of a 1986 commission from George Clinton for Guitar International and was published beside an interview with Koshkin in the magazine that year. Dedicated to his instrument, Guitar is a melodically graceful piece in 3/4, a slow waltz drawn from a simple, upwardly yearning four-note motif.

An early example of Koshkin's desire to exploit 'the impressionistic possibilities' of his instrument is Rain, composed in 1974. As with many Koshkin pieces, it is programmatic. The program here depicts a gentle rain that becomes a torrent, then a major storm, then a few vestigial drops. Koshkin had in mind as vague models some of the water-oriented piano pieces of Debussy and Ravel, but his approach is wholly idiomatic to the guitar. Freely structured, written without barlines, Rain conjures the initial muttering of its subject matter by playing on a combination of closed and open strings, and goes on to press the guitar dynamically and texturally. 'It was my first attempt to make a cinematic effect,' the composer recalls.

The hours between midnight and 3 A.M. are 'a mystical time of dark forces' in Russian fairytales, Koshkin notes. That is when the metaphysical program to Koshkin's Piece with Clocks (1980) takes place. A highly colored work, Piece with Clocks was written immediately after The Prince's Toys (see below) and climaxes the period of the composer's fascination with the musical possibilities of timbral effects. The score starts out and ends up looking like some sort of musical spreadsheet. The effect is of multiple clocks ticking (Tempo di tick-tock is the indication), produced by quasi-harmonics on the first and second strings. These are punctuated by the sound of clock bells tolling, an aural illusion produced by placing matchsticks between the strings, a device inspired, says Koshkin, by the American avant-gardist John Cage's 'prepared piano.' As Cage would 'prepare' a piano with bits of erasers or other objects in the strings to alter timbre, Koshkin's Piece with Clocks calls at various times for placing matchsticks, cork, and an unusual foam mute. The 'dark forces' evinced culminate in a chilling fugato passage that falls away to leave the tick-tocking of merciless time untouched by humanity's concerns.

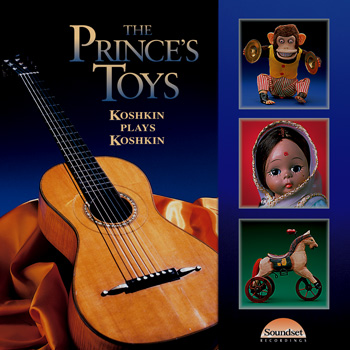

Koshkin feared he would be 'writing the same piece all my life' when, in 1980, he put aside The Prince's Toys after six years of labor. Begun in 1974, the suite had at one point contained 12 movements. Its genesis was a desire to achieve the integration of technical and coloristic effects with musical expression. To do that, Koshkin needed an aesthetic excuse, an artistic reason to include a very broad range of effects both standard and newly invented. Once more, he found his linchpin in a program.

'The title actually came before the program,' Koshkin says. The idea of a prince whose toys came alive and 'fought back,' playing with him in the same mischievous way he had played with them, flowed naturally from the title and suited Koshkin's purpose perfectly. Suggesting somewhat the singing and dancing toys of Ravel's L'Enfant et les sortileges, the four toys of Koshkin's prince are actually more demonic for seeming more innocent. The movements of The Prince's Toys are as follow:

The Mischievous Prince. The title character is portrayed by a short, aggressive piece filled with parallel ninths and other stacked dissonances. Percussive, unpitched arpeggios on all six strings (on the bridge behind the saddle) punctuate the end.

The Mechanical Monkey. The slapping of strings and drumming of fingers on the guitar's body suggest the angular motions of a toy monkey who has an eerie agenda: revenge on the prince who has abused him.

The Doll with Blinking Eyes is an East Indian doll, the likeness of a beautiful young woman. 'The most mystical of the six movements,' according to the composer, The Doll contains several unique effects, including a sitar-like buzzing produced by pulling and holding the sixth string off to the side of the guitar. The Indian drum called the tabla is also imitated, by striking the bridge.

Playing Soldiers. Although translated as 'Tin Soldiers' in the published music, this movement's original Russian title emphasizes the process of interaction with toy soldiers more than the material from which they're made. In the course of the movement, the toy soldiers become real. This is made musically palpable by what Koshkin calls 'a developed effect.' The movement begins with the sound of a toy drum and trumpet, but as the soldiers become real, the effect becomes 'real as well,' and a more sonorous drum-and-trumpet is conveyed. At one point in the development, the guitarist must play an extensive left-hand solo while the right hand crosses over the left in a percussive dialogue between thumping drums (hand near the bridge) and tinkling bells (the section of the strings between the tuners and nut, strummed).

The Prince's Coach. The blissful theme of the prince's escape is heard above the running pattern of the coach's wheels. At first, it seems the prince will make it, but something goes terribly wrong and the horses begin to gallop with such ferocity that they break away from the coach, leaving the prince stranded. Their galloping is depicted by the tapping of fingers on the side of the instrument.

The Grand Toys' Parade is 'a suite within the suite,' Koshkin says. A set of variations on a melancholy theme that represents the chastised prince, it also recalls subjects from the previous movements. The movement and the suite end with a long, thumbnail glissando; the prince, defeated, has been turned into one of the toys.

Koshkin read Edgar Allen Poe's short story, The Fall of the House of Usher, at age 12. It had a profound and lingering effect on him. The passage in which the main character improvises a waltz on a theme of Weber came back to haunt Koshkin, after a fashion, when he began to compose. Determined to compose a concert waltz 'in the tradition of Tchaikovsky, Rachmaninoff and Shostakovich' conjuring the sense of voluptuous decay in the story, Koshkin decided not to base his waltz on an actual Weber theme, but to write a complete original in 'stylized Romantic' manner. The result, Usher-Waltz (1984), is both beautiful and demonic, as well as devilish to play. A six-note motif, gentle at the outset, is transmogrified over the course of the waltz. The motif (which outlines an ascending diminished triad, topped by a minor ninth that resolves down to the diminished seventh) surrounds and suggests the key of A minor without baldly stating it. The working-out of the motif explores various diminished, minor and quartal harmonies, in textures ranging from wispy-thin to pianistically full-blooded. Made popular by a number of guitarists including John Williams, Usher-Waltz is to Koshkin as the G-sharp minor Prelude was to Rachmaninoff.

-- Kenneth LaFave

Amazon

Amazon