Review of Anthony Newman's Complete Works, Marc Medwin

Anthony Newman is "the high priest of Bach," proclaims nearly everyone discussing the keyboardist's fifty-year career as a forefront interpreter of Bach's organ, harpsichord and orchestral works. The appellation has been with Newman since the late 1960s, when a Time Magazine article dubbed him "the high priest of the harpsichord," a riff transformed later by Wynton Marsalis into the one by which he is so ubiquitously known today. It was through Newman's Bach that I first came to hear and admire his musicmaking, renderings of these well-thumbed and oft-executed scores that blew the proverbial cobwebs far enough away to be forgotten. The 2013 release of two Bach box sets on Newman's own 903 Records, one containing the majority of Bach's organ works and one dedicated to his harpsichord pieces, demonstrate a player of extraordinary virtuosity in the service of an equally penetrating intellect and open spirit, a reasoning mind coming to terms with music of awe-inspiring construction and the highest emotional import.

Newman and I began to correspond, by Email and phone, and the vibrancy and introspection that comprise his personality became abundantly clear. It also turned out that another 20-cd set was in the immediate offing, containing all of Newman's important compositions since the middle 1980s. Far from someone trapped in the baroque era or unwilling to engage with anything approaching modernity, what emerged in our conversations and from my listening is what I'll call the picture of a complete musician - a performer, a conductor and a composer who's total grasp of music's history, and of much that has been written concerning the multifarious relationships governing that history's progression is formidable, a surprise in all manner of expression lurking around every corner.

"I upset a lot of people in those early days." Newman's delivery is almost nonchalant, a grin lurking just beneath each word. "When I came up with the ideas concerning tempo and ornamentation, as well as playing much more quickly than is usual on the organ, ideas that I use to this day, a lot of the traditionalists were up in arms." The oft-cited example is Newman's realization of Bach's B-Minor organ prelude, BWV 544, in which his dotted rhythmic approach is augmented by liberal use of ornamentation. Newman demonstrates the contrast on an electric keyboard that happens to be at hand during our conversation, the spring and vibrancy of his realization more than palpable coming through the tiny phone speaker over miles of cable and circuitry. "Composers always wrote less than they played at that time," he begins, referencing copies made by Bach students in which ornamentation is plentiful. "So what happened," he muses, "The students ornamented only when Bach was out of town? That's ridiculous! The only other logical explanation is that Bach played this way, and convention dictated that it wasn't necessary to write it all down." Newman points out that many of the ornaments found in late baroque and classical period sources, including those in Mozart's hand obviously meant for teaching purposes, are much more adventurous than anyone today would dare to attempt. "If you ornamented like that on your own, a teacher would reject them, it's that simple." Newman's rhythmic presentation gave the prelude an entirely different feel. In an Email, he explains that the practice "cathects to an old French tradition seen in Couperin of restarting the dotted notes after cadences, when the dotting stops for a brief moment. It's discussed in my book' Bach and the Baroque.' It has always got me in trouble with the traditional Organ crowd."

The road to such a vital and engaging performance style was long but full of extraordinary moments of discovery, and it leads far beyond Bach. When listening to Newman's breathtaking pedal harpsichord recordings, such as his take on the C-Minor Passacaglia and Fugue (BWV565) or delving into his energetic interpretation of the Goldberg's, the third of several in his recorded output, it is easy to imagine that Bach is his specialty. That would explain the emotional import of the 15th variation, despite its comparatively rapid tempo and a recording whose ambiance leaves relatively little room in which to breathe. While Bach is certainly at the heart of Newman's musical life, a fearless reading of Beethoven's piano concertos, replete with extras like Mozart's oft-played C-minor Fantasy and Beethoven's own similarly whimsical fantasy for chorus and orchestra, speaks to a much broader vision of period practice and of the history guiding it. Like much of his Bach, faster movements in his Beethoven and Mozart are on the quick side without ever being breathless, spritely without letting speed and energy supplant imagination and gestural clarity. Nonetheless, through it all comes a sense of playful spontaneity as he ornaments, not just in the conventional ways and at repeats, about which he can be cavalier; for Newman, improvisation is an aesthetic--a phrase unexpectedly elongated, a rhythm expanded, the first note of a measure delayed to startling effect.

Nothing sums up Newman's years of dedication and study as succinctly as a conversation with him, and speaking at length about literature, musicology and matters of the spirit is an enlightening experience. Perhaps halfway through our talk came the offhanded comment, "You know, there's about to be a twenty-disc set of my own compositions, basically things I've written since 1985 with a few earlier works included …" A composer? It was then that a whole other aspect of Newman's musical journey began to be revealed, from his late-teenage studies in Paris with Nadia Boulanger, assistantship to Luciano Berio as a Harvard student, his appreciation of Stravinsky and serious issues with twelve-tone composition, and his fascinating and very complex views on tonality vs. atonality, which can be read in his newsletter. Newman's trajectory as a musician is one that cannot really be understood without immersion in his piano sonatas, organ symphonies, his opera concerning the O.J. Simpson trial and so many other pieces of remarkable originality.

In a 2011 episode of Pipedreams, Newman describes his compositional language as a mixture of baroque rhetoric with harmonies out of Stravinsky. In the notes accompanying his new twenty-disc set, he writes: "None of my music really crosses the border of tonality but sometimes flirts with it. I believe that new music must have some kind of memorable melody and some kind of harmonic background to be truly worthy." While there is truth in Newman's own assessment of his music, it fails to account for the wit, rhythmic and textural imagination and deep feeling imbuing these works by turn.

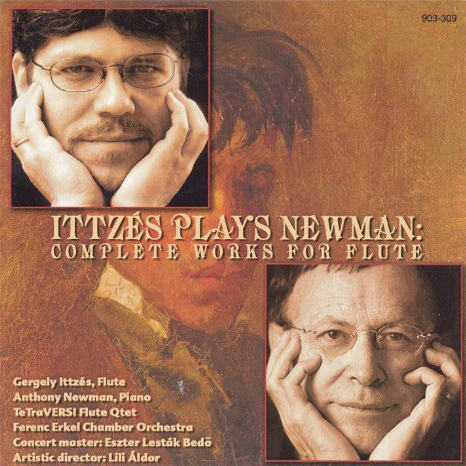

Newman's concerto for flute and orchestra is a case in point, combining some of the oldest contrapuntal devices with surprisingly modern narrative structures. Presented in a live recording with Gergely Ittzes expertly handling the solo part, the opening movement might first appear as a study in Mozartian elegance. Below the surface though, the canonic opening coexists with a neoclassical language with which Poulenc would have been quite at home, possibly a reflection of Newman's studies in France. Harmonic changes abound, rhythmic accents are subtle but poignant, and deeper listening reveals something of a Russian flavor, returning a listener's thoughts to aspects of Stravinsky's long neoclassical period. The recording (which appears twice in my set, though I'm told this oversight will be corrected) is atmospheric without loss of perspective, a very nice live taping of music that thrives on the subtlety of exposure to every detail.

A fascinating comparison is to be made between a relatively recent work such as the flute concerto and "Jonah and the Wale," composed in the middle 1960s for piano and violin. "I've never thought that serialism could achieve any lasting emotional impact," Newman muses as we discuss his musical language of that time. "It was necessary for me to create my own version of atonality without using the twelve-tone method." Newman disavows most of the music he wrote in what he seems to view as a darkly tyrannical point in modern music's history, but hearing the beautifully melodic yet pantonal writing in "Jonah," it's difficult to understand why. Its soundworld is somewhat akin to Berg, or perhaps to very early Webern, and the performance by Newman and violinist Bruce Berg is nuanced and obviously emotionally committed. Occasionally, as in the opening movement of the sonata titled "My Country 'Tis," Newman still pushes at the boundaries of tonality, but it would be fair to say that his compositional language is more user-friendly these days without ever becoming trite.

Three large sets in a single year seemed quite a lot to digest at once. "Yes," Newman laughs, "but it was important to me that it happen this way. I'd reached an important point of completion in my spiritual studies, and now seemed like the perfect time for summing up." When taken as a whole, these thirty-nine discs do indeed present a unified picture of a questing musician, one for whom, as with Edgard Varèse, the past is always present, but not as a burden; it is something to be reexamined and celebrated. At 72, Newman shows no signs of resting on his considerable accomplishments. These sets appear as a moment of reflection, but the speed and precision with which he speaks, so similar to those qualities in his playing, remain unimpeded, each answer leading to deeper questions, the answers to come, no doubt, in what promises to be an equally rich future.

Anthony Newman is "the high priest of Bach," proclaims nearly everyone discussing the keyboardist's fifty-year career as a forefront interpreter of Bach's organ, harpsichord and orchestral works. The appellation has been with Newman since the late 1960s, when a Time Magazine article dubbed him "the high priest of the harpsichord," a riff transformed later by Wynton Marsalis into the one by which he is so ubiquitously known today. It was through Newman's Bach that I first came to hear and admire his musicmaking, renderings of these well-thumbed and oft-executed scores that blew the proverbial cobwebs far enough away to be forgotten. The 2013 release of two Bach box sets on Newman's own 903 Records, one containing the majority of Bach's organ works and one dedicated to his harpsichord pieces, demonstrate a player of extraordinary virtuosity in the service of an equally penetrating intellect and open spirit, a reasoning mind coming to terms with music of awe-inspiring construction and the highest emotional import.

Newman and I began to correspond, by Email and phone, and the vibrancy and introspection that comprise his personality became abundantly clear. It also turned out that another 20-cd set was in the immediate offing, containing all of Newman's important compositions since the middle 1980s. Far from someone trapped in the baroque era or unwilling to engage with anything approaching modernity, what emerged in our conversations and from my listening is what I'll call the picture of a complete musician - a performer, a conductor and a composer who's total grasp of music's history, and of much that has been written concerning the multifarious relationships governing that history's progression is formidable, a surprise in all manner of expression lurking around every corner.

"I upset a lot of people in those early days." Newman's delivery is almost nonchalant, a grin lurking just beneath each word. "When I came up with the ideas concerning tempo and ornamentation, as well as playing much more quickly than is usual on the organ, ideas that I use to this day, a lot of the traditionalists were up in arms." The oft-cited example is Newman's realization of Bach's B-Minor organ prelude, BWV 544, in which his dotted rhythmic approach is augmented by liberal use of ornamentation. Newman demonstrates the contrast on an electric keyboard that happens to be at hand during our conversation, the spring and vibrancy of his realization more than palpable coming through the tiny phone speaker over miles of cable and circuitry. "Composers always wrote less than they played at that time," he begins, referencing copies made by Bach students in which ornamentation is plentiful. "So what happened," he muses, "The students ornamented only when Bach was out of town? That's ridiculous! The only other logical explanation is that Bach played this way, and convention dictated that it wasn't necessary to write it all down." Newman points out that many of the ornaments found in late baroque and classical period sources, including those in Mozart's hand obviously meant for teaching purposes, are much more adventurous than anyone today would dare to attempt. "If you ornamented like that on your own, a teacher would reject them, it's that simple." Newman's rhythmic presentation gave the prelude an entirely different feel. In an Email, he explains that the practice "cathects to an old French tradition seen in Couperin of restarting the dotted notes after cadences, when the dotting stops for a brief moment. It's discussed in my book' Bach and the Baroque.' It has always got me in trouble with the traditional Organ crowd."

The road to such a vital and engaging performance style was long but full of extraordinary moments of discovery, and it leads far beyond Bach. When listening to Newman's breathtaking pedal harpsichord recordings, such as his take on the C-Minor Passacaglia and Fugue (BWV565) or delving into his energetic interpretation of the Goldberg's, the third of several in his recorded output, it is easy to imagine that Bach is his specialty. That would explain the emotional import of the 15th variation, despite its comparatively rapid tempo and a recording whose ambiance leaves relatively little room in which to breathe. While Bach is certainly at the heart of Newman's musical life, a fearless reading of Beethoven's piano concertos, replete with extras like Mozart's oft-played C-minor Fantasy and Beethoven's own similarly whimsical fantasy for chorus and orchestra, speaks to a much broader vision of period practice and of the history guiding it. Like much of his Bach, faster movements in his Beethoven and Mozart are on the quick side without ever being breathless, spritely without letting speed and energy supplant imagination and gestural clarity. Nonetheless, through it all comes a sense of playful spontaneity as he ornaments, not just in the conventional ways and at repeats, about which he can be cavalier; for Newman, improvisation is an aesthetic--a phrase unexpectedly elongated, a rhythm expanded, the first note of a measure delayed to startling effect.

Nothing sums up Newman's years of dedication and study as succinctly as a conversation with him, and speaking at length about literature, musicology and matters of the spirit is an enlightening experience. Perhaps halfway through our talk came the offhanded comment, "You know, there's about to be a twenty-disc set of my own compositions, basically things I've written since 1985 with a few earlier works included …" A composer? It was then that a whole other aspect of Newman's musical journey began to be revealed, from his late-teenage studies in Paris with Nadia Boulanger, assistantship to Luciano Berio as a Harvard student, his appreciation of Stravinsky and serious issues with twelve-tone composition, and his fascinating and very complex views on tonality vs. atonality, which can be read in his newsletter. Newman's trajectory as a musician is one that cannot really be understood without immersion in his piano sonatas, organ symphonies, his opera concerning the O.J. Simpson trial and so many other pieces of remarkable originality.

In a 2011 episode of Pipedreams, Newman describes his compositional language as a mixture of baroque rhetoric with harmonies out of Stravinsky. In the notes accompanying his new twenty-disc set, he writes: "None of my music really crosses the border of tonality but sometimes flirts with it. I believe that new music must have some kind of memorable melody and some kind of harmonic background to be truly worthy." While there is truth in Newman's own assessment of his music, it fails to account for the wit, rhythmic and textural imagination and deep feeling imbuing these works by turn.

Newman's concerto for flute and orchestra is a case in point, combining some of the oldest contrapuntal devices with surprisingly modern narrative structures. Presented in a live recording with Gergely Ittzes expertly handling the solo part, the opening movement might first appear as a study in Mozartian elegance. Below the surface though, the canonic opening coexists with a neoclassical language with which Poulenc would have been quite at home, possibly a reflection of Newman's studies in France. Harmonic changes abound, rhythmic accents are subtle but poignant, and deeper listening reveals something of a Russian flavor, returning a listener's thoughts to aspects of Stravinsky's long neoclassical period. The recording (which appears twice in my set, though I'm told this oversight will be corrected) is atmospheric without loss of perspective, a very nice live taping of music that thrives on the subtlety of exposure to every detail.

A fascinating comparison is to be made between a relatively recent work such as the flute concerto and "Jonah and the Wale," composed in the middle 1960s for piano and violin. "I've never thought that serialism could achieve any lasting emotional impact," Newman muses as we discuss his musical language of that time. "It was necessary for me to create my own version of atonality without using the twelve-tone method." Newman disavows most of the music he wrote in what he seems to view as a darkly tyrannical point in modern music's history, but hearing the beautifully melodic yet pantonal writing in "Jonah," it's difficult to understand why. Its soundworld is somewhat akin to Berg, or perhaps to very early Webern, and the performance by Newman and violinist Bruce Berg is nuanced and obviously emotionally committed. Occasionally, as in the opening movement of the sonata titled "My Country 'Tis," Newman still pushes at the boundaries of tonality, but it would be fair to say that his compositional language is more user-friendly these days without ever becoming trite.

Three large sets in a single year seemed quite a lot to digest at once. "Yes," Newman laughs, "but it was important to me that it happen this way. I'd reached an important point of completion in my spiritual studies, and now seemed like the perfect time for summing up." When taken as a whole, these thirty-nine discs do indeed present a unified picture of a questing musician, one for whom, as with Edgard Varèse, the past is always present, but not as a burden; it is something to be reexamined and celebrated. At 72, Newman shows no signs of resting on his considerable accomplishments. These sets appear as a moment of reflection, but the speed and precision with which he speaks, so similar to those qualities in his playing, remain unimpeded, each answer leading to deeper questions, the answers to come, no doubt, in what promises to be an equally rich future.