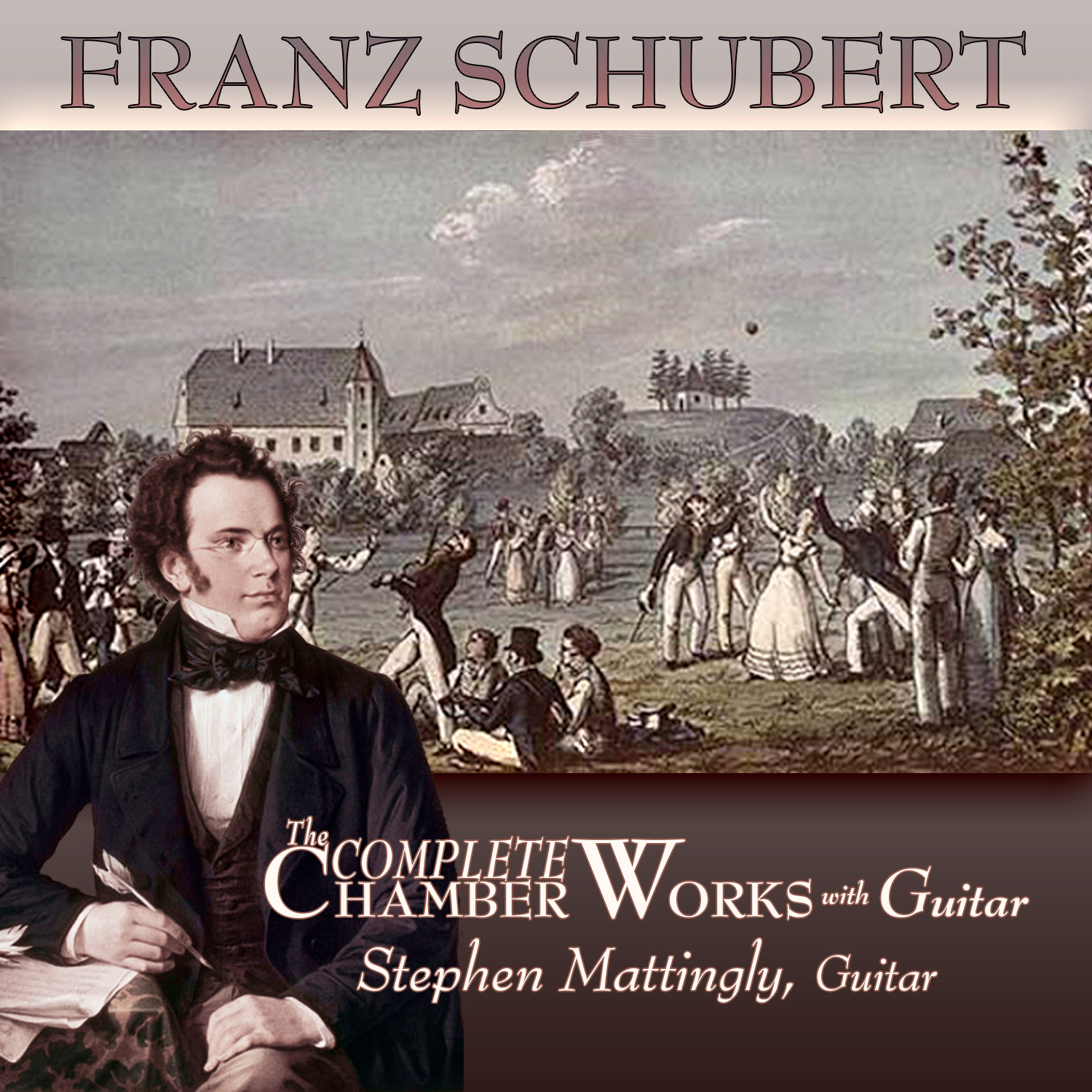

On the Cover

Schubert’s artistic contemporaries often depicted him performing for his friends’ at the Atzenbrugg palace outside Vienna. These outings usually included light sport, games, and dancing accompanied by the guitar and violin. One such festival at Atzenbrugg inspired Schubert to compose his Atzenbrugg Dances for piano, Op. 33 and Op. 9; a set of 15 waltzes from Op. 9 were arranged for violin and guitar and published during Schubert’s life. Schubert was certainly familiar with this duo as seen in the cover art. Here the composer is seated next to a guitarist as a violinist plays before them. This etching is titled Ballspiel in Atzenbrugg by Ludwig Mohn (1820), and is based on a composite drawing by Franz von Schober, who sketched the background, and Moritz von Schwind, who drew the figures in the foreground. This piece is significant because both Schober and Schwind were close friends to Schubert.

The Guitar in Biedermeier Vienna:

During Schubert’s lifetime, Vienna was enjoying a more carefree social lifestyle of post-war celebration, referred to as the Biedermeier period. At this time, citizens among the growing middle-class experienced systems of censorship that discouraged public discussion of the oppressive ruling class. In stark contrast to the harsh political environment, Biedermeier social life was characterized by an air of optimism and relaxed, bourgeois socializing that lasted from 1815-1848 and strongly influenced the course of daily life in Vienna. Amidst this casual atmosphere was the ever-present sound of a new, lighthearted, musical tradition that included songs, dances, and serenades accompanied by the increasingly popular guitar.

Before considering the guitar’s direct significance to Schubert, it is important to note that in the early nineteenth century, the guitar enjoyed remarkable popularity among upper and middle-class society throughout Europe. Notable composers from across the continent provided guitar works for this resounding public demand. In his dissertation on Mauro Giuliani, Thomas Heck cited Vienna as the source of the modern classic guitar’s birth and cultivation. Given the guitar’s frequent use in vocal accompaniment and Schubert’s exposure to the instrument, it seems natural to consider his relationship with the instrument.

The most controversial point about Schubert’s relationship with the guitar lies in the fundamental question of whether he played the instrument. Due to unsubstantiated assumptions by guitar enthusiasts such as A. P. Sharpe, fictitious statements have filled the gaps in music history and cast Schubert as a practicing guitarist who relied upon the instrument to compose. In his Schubert biography, Sharpe states that “For years Franz Schubert, not possessing a piano, did most of his composing on the guitar which hung over his bed and on which he would play before rising.” Sharpe’s infamous quote is not supported by evidence in any form and amounts to nothing more than myth. A class mate at the Imperial Seminary, Anton Stadler, confirms that Schubert composed at the desk with no piano and no guitar.

According to Kay Griffen Belangia, estate records show that Schubert owned two guitars during his life.[1] Other sources including Spring Ulrike at the Vienna Museum and the Vienna Schubertbund have confirmed this report. The Vienna Museum has one of these guitars in its collection; an instrument built in c.1805 by Bernard Enzensperger. The Vienna Schubertbund has a guitar built in 1815 by Johann Georg Staufer that was in Schubert’s possession.

Schubert’s Repertoire with the Guitar

Manuscripts and Works Published/Arranged: 1797-1828

In the nineteenth century, it was common to allow publishing houses to make guitar arrangements of vocal accompaniments. Not only was the guitar closely associated with vocal accompaniment, but the public demand for so-called Haus Musik made the inexpensive scores an excellent promotional tool for any composer’s career. Finally, there is sound documentation that the guitar was frequently used to accompany Schubert’s part-songs and Lieder in Schubert’s presence.

There is primary source material proving that Schubert wrote for the guitar. The following works exist in manuscript with guitar accompaniment: Terzetto, D. 80, Quartetto, D. 96, and Das Dörfchen, D. 598a. This first version of Das Dörfchen is not included in the First Complete Schubert Edition and is not featured on my recording of Schubert’s complete chamber music with guitar. In place of this version is the second version (Das Dörfchen, D. 598b) which is featured in the Schubert Edition as Op. 11, no. 1. The editions compiled and edited for this recording will be available in print soon.

Works for Male Voice Trio and Quartet

Schubert composed several part-songs with guitar accompaniment included in the published score. These works were the focus of Richard Long’s article Schubert’s “Lost” Works for Guitar (Soundboard; Spring, 2002). For Schubert, most of these pieces were intended for ‘a capella’ performance. Although professional choirs and vocal ensembles would easily perform the works ‘a capella’ after regular rehearsal, accompaniment was needed for impromptu performances and amateur gatherings. Johann Herbeck, in his introduction to the New Edition of Choruses by Franz Schubert; published by C. A. Spina in 1865, relates that during Schubert’s time “changes were made to the accompaniment as needed” and that “it doesn’t matter which accompaniment form one uses whether you are met with a piano or a guitar.” More remarkable is his observation that “Schubert himself thought of the accompaniment more as a harmonic basis or simple support of the voices…”[2] This sentiment was shared by one Biedermeier singer who writes: “If an instrumental accompaniment is given, then one uses it to perform on a cembalo, piano, guitar or whatever…if an instrumental accompaniment is missing, then it would be improvised.”[3]

In the first Complete Schubert Edition published by Breitkopf and Härtel, editors Eusebius Mandezewski and Johannes Brahms decided to include the previously published guitar accompaniments with these vocal quartets.[4] The select works that were published in the First Complete Schubert Edition with guitar accompaniment are from Op. 11 and Op. 16. The works for male quartet that make up Schubert’s Op. 11 are Das Dörfchen (D. 598b)[5], Die Nachtigall (D. 784), and Geist der Liebe (D. 747). Geist der Liebe was performed at a Gesellschaft concert on March 3rd, 1822 and again on August 27th, 1822 with the guitar accompaniment played by a Mr. Schmidt.[6] Guitarists such as Johann Umlauff participated in the first performances of these works.[7] At a more intimate gathering, Mauro Giuliani was among the company that formed male voice quartets.[8] The publication of Op. 16 including Naturgenuss (D. 422) and Frühlingsgesang (D. 740) carried the words “mit willkülicher Begleitung des Pianoforte oder Guitarre” (with obbligato accompaniment of piano or guitar).

Schubert had undoubtedly attained some level of understanding the guitar when he completed a Terzetto, D. 80 for two tenors, and bass, with guitar accompaniment on September 27th, 1813. This work is one of his earliest for male voices. Also titled Kantate by Schubert, this work was dedicated to the honor of his father’s name day in Schubert’s own words at the end of the manuscript: “zur Namensfeier meines Vaters”. Reliable sources backed by previous investigation show the premier was given on October 4th, 1813 by brothers Ignaz, Karl, and Ferdinand accompanied by Franz on the guitar.[9] Some scholars believe this was not the only instance in which Schubert accompanied his brothers on the guitar.[10]

It is interesting that documented performances of these works included only one man on each part. No standard doubling was practiced for the performance of the vocal quartets during this time. It seems, however, that Schubert’s works were usually performed by soloists. This partitioning recalls the group of students with whom Schubert sang during his studies at the Seminary and allows greater dynamic balance with guitar accompaniment.

Original Dances, D. 365 (1816-July 1821):

Diabelli’s Arrangement

The character of these works is at the heart of Schubert’s Biedermeier experiences. However, they belie the masterful abilities of the composer with their characteristic Biedermeier simplicity in their use of simple homophonic texture and bucolic, folk-like melodies. These works were arranged for violin and guitar from the Atzenbrugg Dances, Op. 9, some believe by Schubert him self. It is more likely however, that Schubert’s publisher, Anton Diabelli, arranged them in similar fashion to the arrangements of Schubert’s Lieder.

Dancing was a common part of all Schubertiads where the composer would often improvise waltzes at the piano for his friends’ enjoyment. The guitar played a central part in the development of the waltz during Schubert’s life. In the Austrian Alps, the Styrians, where the waltz was popularized, musicians performed waltzes in ensembles comprised of violins, clarinets, guitar, and bass. Famed waltz composer Joseph Lanner performed his waltzes in ensembles with guitar and violin.

Quartetto, D. 96

Further contact with the guitar and compositions for the instrument came through the quartet Schubert’s father held with his friends.[11] It was for this ensemble that Schubert arranged Matiegka’s Noturno, Op. 21 by rewriting significant portions and adding a cello part to the work originally for flute, viola, and guitar. The original was published in Vienna by Artaria and Company in 1807, seven years before Schubert dated his manuscript “February 27th, 1814.” Hints to the origins of Schubert’s arrangement are found throughout the work, most notably on the title page where Schubert began to write the word “Terzetto,” crossed out this and wrote in his own title “Quartetto.” Schubert did not however make any direct note of Matiegka’s original title Noturno. He indicated, nevertheless that several variations in the final movement would remain the “same as in the printed trio.”

Comparative analysis of guitar’s role in the second Trio with the surrounding movements, suggests Schubert’s true capabilities as a guitarist. In the Trio II Schubert’s original writing for the guitar reverts to the more simple arpeggiated figures and block chords like those found in the Terzetto, D. 80. The reduced texture of the guitar part indicates Schubert perception of its position in the ensemble, and provides solid evidence of Schubert’s narrow, yet capable knowledge of the instrument.

Works for Solo Voice and Guitar: Die Nacht, WoO (c. 1840)

Between 1840 and 1842 Schubert’s friend and colleague, Franz von Schlechta arranged and copied works for his own performance on the guitar. In all there are 99 volumes dedicated to guitar music for solo, duo, and vocal accompaniment. While only a few works are included by famous Viennese composers such as Beethoven, Mozart, and Haydn, Schubert’s works span 39 volumes (51-89) in this project.[12] Die Nacht is one work included in this collection. Upon first glance this manuscript seems to be the only surviving Lied with original guitar accompaniment, but after closer investigation the evidence supporting such claims takes on a more complex form. Most interesting in Schlechta’s copy is that, lying easily on the instrument, the accompaniment seems as if it were originally conceived for the guitar.[13] However, the same Lied appears at the end of the volume transposed to C major. Here, additional text on the title page states that the work was “arranged by J. N. Huber”, a known guitar arranger in Vienna during Schubert’s lifetime.[14] This may refer to the arrangement of a lost piano manuscript or simply to the transposition from the original key. In any case, this Lied’s contribution to the understanding of the guitar’s place as an accompanying instrument is immeasurable.

About the Artists

The musicians featured on this recording include faculty and students from the Florida State University College of Music. Their dedicated efforts help make Florida State University one of the preeminent sources of musical excellence in the United States.

This project was funded in part by a grant from the Theodore Presser Foundation. For further information on the subject of Franz Schubert and the guitar, please refer to Dr. Mattingly’s treatise, “Franz Schubert’s Chamber Music with Guitar: A Study of the Guitar’s Role in Biedermeier Vienna,” available online.

Special thanks to Kris Anderson, Seth Beckman, Larry Gerber, Thomas Heck, Bruce Holzman, Richard Long, John Reed, Leo Welch, and especially the Theodore Presser Foundation.

Cover art reproduced with kind permission from the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Vienna. The graphic art design is by Leanne Koonce.

End Notes:

1 Belangia, Kay Griffin. The Influence of the Guitar and the Biedermeier Culture on Franz Schubert’s Vocal Accompaniments. Dissertation: Master’s Thesis, East Carolina University, 1983, p. 33.

2 Berke, Dietrich. Franz Schubert: Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke. Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1974. p. xxii.

3 Dürr, Walther and Andreas Krause. Schubert-Handbuch. Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1997, p. 278.

4 Mandyczewski, Brahms, et al. Franz Schubert: Complete Works. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1897. Vol. 16.

5 Formerly listed as D. 641 in the Schubert Thematic Catalogue, this work is now referenced as D. 598b. See Brown, Maurice John Edwin with Eric Sams. “Schubert, Franz” (work-list), Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 21 December 2005),

6 Deutsch in Reinhard van Hoorickx, Schubert’s Guitar Quartet, D. 96, Revue belge de Musicologie. Vol. 31 (March-April 1977), p. 122.

7 Flower, Newman. Franz Schubert: The Man and his Circle. New York: Tudor Publishing, 1936, p. 345.

8 Ibid., p. 335.

9 Deutsch, Otto E., and Wakeling, Donald R. Schubert Thematic Catalogue of all His Works. New York: Edwin F. Kalmus, 1950, p. 33.

10 Schneider, Marcel. Franz Schubert. In Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten, aus: rowahlts Monographien, herausgegeben von Kurt Kusenberg. Hamburg: 1968. Cited in Schult, Vike, p. 31.

11 Kinsky, Georg. Forward to the Published Edition of the Quartet D. 96. New York: C. F. Peters, 1956.

12 Scheit, Karl and Partsch, Erich Wolfgang. Ein unbekanntes SchubertLied in einer Sammlung aus dem Wiener Vormärz. Schubert durch die Brille: Internationales Franz Schubert Institut Mitteilungen, No. 2 (January, 1989), p. 15.

13 Ahrens, Christian. Zur Rezeption der Gitarre in Deutschland im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Bach & Schubert: Beiträge zur Musikforschung, Jahrbuch der Bachwoche Dillenburg, (1999): Vol. 33, p. 27

14 Scheit, p. 18

Schubert’s artistic contemporaries often depicted him performing for his friends’ at the Atzenbrugg palace outside Vienna. These outings usually included light sport, games, and dancing accompanied by the guitar and violin. One such festival at Atzenbrugg inspired Schubert to compose his Atzenbrugg Dances for piano, Op. 33 and Op. 9; a set of 15 waltzes from Op. 9 were arranged for violin and guitar and published during Schubert’s life. Schubert was certainly familiar with this duo as seen in the cover art. Here the composer is seated next to a guitarist as a violinist plays before them. This etching is titled Ballspiel in Atzenbrugg by Ludwig Mohn (1820), and is based on a composite drawing by Franz von Schober, who sketched the background, and Moritz von Schwind, who drew the figures in the foreground. This piece is significant because both Schober and Schwind were close friends to Schubert.

The Guitar in Biedermeier Vienna:

During Schubert’s lifetime, Vienna was enjoying a more carefree social lifestyle of post-war celebration, referred to as the Biedermeier period. At this time, citizens among the growing middle-class experienced systems of censorship that discouraged public discussion of the oppressive ruling class. In stark contrast to the harsh political environment, Biedermeier social life was characterized by an air of optimism and relaxed, bourgeois socializing that lasted from 1815-1848 and strongly influenced the course of daily life in Vienna. Amidst this casual atmosphere was the ever-present sound of a new, lighthearted, musical tradition that included songs, dances, and serenades accompanied by the increasingly popular guitar.

Before considering the guitar’s direct significance to Schubert, it is important to note that in the early nineteenth century, the guitar enjoyed remarkable popularity among upper and middle-class society throughout Europe. Notable composers from across the continent provided guitar works for this resounding public demand. In his dissertation on Mauro Giuliani, Thomas Heck cited Vienna as the source of the modern classic guitar’s birth and cultivation. Given the guitar’s frequent use in vocal accompaniment and Schubert’s exposure to the instrument, it seems natural to consider his relationship with the instrument.

The most controversial point about Schubert’s relationship with the guitar lies in the fundamental question of whether he played the instrument. Due to unsubstantiated assumptions by guitar enthusiasts such as A. P. Sharpe, fictitious statements have filled the gaps in music history and cast Schubert as a practicing guitarist who relied upon the instrument to compose. In his Schubert biography, Sharpe states that “For years Franz Schubert, not possessing a piano, did most of his composing on the guitar which hung over his bed and on which he would play before rising.” Sharpe’s infamous quote is not supported by evidence in any form and amounts to nothing more than myth. A class mate at the Imperial Seminary, Anton Stadler, confirms that Schubert composed at the desk with no piano and no guitar.

According to Kay Griffen Belangia, estate records show that Schubert owned two guitars during his life.[1] Other sources including Spring Ulrike at the Vienna Museum and the Vienna Schubertbund have confirmed this report. The Vienna Museum has one of these guitars in its collection; an instrument built in c.1805 by Bernard Enzensperger. The Vienna Schubertbund has a guitar built in 1815 by Johann Georg Staufer that was in Schubert’s possession.

Schubert’s Repertoire with the Guitar

Manuscripts and Works Published/Arranged: 1797-1828

In the nineteenth century, it was common to allow publishing houses to make guitar arrangements of vocal accompaniments. Not only was the guitar closely associated with vocal accompaniment, but the public demand for so-called Haus Musik made the inexpensive scores an excellent promotional tool for any composer’s career. Finally, there is sound documentation that the guitar was frequently used to accompany Schubert’s part-songs and Lieder in Schubert’s presence.

There is primary source material proving that Schubert wrote for the guitar. The following works exist in manuscript with guitar accompaniment: Terzetto, D. 80, Quartetto, D. 96, and Das Dörfchen, D. 598a. This first version of Das Dörfchen is not included in the First Complete Schubert Edition and is not featured on my recording of Schubert’s complete chamber music with guitar. In place of this version is the second version (Das Dörfchen, D. 598b) which is featured in the Schubert Edition as Op. 11, no. 1. The editions compiled and edited for this recording will be available in print soon.

Works for Male Voice Trio and Quartet

Schubert composed several part-songs with guitar accompaniment included in the published score. These works were the focus of Richard Long’s article Schubert’s “Lost” Works for Guitar (Soundboard; Spring, 2002). For Schubert, most of these pieces were intended for ‘a capella’ performance. Although professional choirs and vocal ensembles would easily perform the works ‘a capella’ after regular rehearsal, accompaniment was needed for impromptu performances and amateur gatherings. Johann Herbeck, in his introduction to the New Edition of Choruses by Franz Schubert; published by C. A. Spina in 1865, relates that during Schubert’s time “changes were made to the accompaniment as needed” and that “it doesn’t matter which accompaniment form one uses whether you are met with a piano or a guitar.” More remarkable is his observation that “Schubert himself thought of the accompaniment more as a harmonic basis or simple support of the voices…”[2] This sentiment was shared by one Biedermeier singer who writes: “If an instrumental accompaniment is given, then one uses it to perform on a cembalo, piano, guitar or whatever…if an instrumental accompaniment is missing, then it would be improvised.”[3]

In the first Complete Schubert Edition published by Breitkopf and Härtel, editors Eusebius Mandezewski and Johannes Brahms decided to include the previously published guitar accompaniments with these vocal quartets.[4] The select works that were published in the First Complete Schubert Edition with guitar accompaniment are from Op. 11 and Op. 16. The works for male quartet that make up Schubert’s Op. 11 are Das Dörfchen (D. 598b)[5], Die Nachtigall (D. 784), and Geist der Liebe (D. 747). Geist der Liebe was performed at a Gesellschaft concert on March 3rd, 1822 and again on August 27th, 1822 with the guitar accompaniment played by a Mr. Schmidt.[6] Guitarists such as Johann Umlauff participated in the first performances of these works.[7] At a more intimate gathering, Mauro Giuliani was among the company that formed male voice quartets.[8] The publication of Op. 16 including Naturgenuss (D. 422) and Frühlingsgesang (D. 740) carried the words “mit willkülicher Begleitung des Pianoforte oder Guitarre” (with obbligato accompaniment of piano or guitar).

Schubert had undoubtedly attained some level of understanding the guitar when he completed a Terzetto, D. 80 for two tenors, and bass, with guitar accompaniment on September 27th, 1813. This work is one of his earliest for male voices. Also titled Kantate by Schubert, this work was dedicated to the honor of his father’s name day in Schubert’s own words at the end of the manuscript: “zur Namensfeier meines Vaters”. Reliable sources backed by previous investigation show the premier was given on October 4th, 1813 by brothers Ignaz, Karl, and Ferdinand accompanied by Franz on the guitar.[9] Some scholars believe this was not the only instance in which Schubert accompanied his brothers on the guitar.[10]

It is interesting that documented performances of these works included only one man on each part. No standard doubling was practiced for the performance of the vocal quartets during this time. It seems, however, that Schubert’s works were usually performed by soloists. This partitioning recalls the group of students with whom Schubert sang during his studies at the Seminary and allows greater dynamic balance with guitar accompaniment.

Original Dances, D. 365 (1816-July 1821):

Diabelli’s Arrangement

The character of these works is at the heart of Schubert’s Biedermeier experiences. However, they belie the masterful abilities of the composer with their characteristic Biedermeier simplicity in their use of simple homophonic texture and bucolic, folk-like melodies. These works were arranged for violin and guitar from the Atzenbrugg Dances, Op. 9, some believe by Schubert him self. It is more likely however, that Schubert’s publisher, Anton Diabelli, arranged them in similar fashion to the arrangements of Schubert’s Lieder.

Dancing was a common part of all Schubertiads where the composer would often improvise waltzes at the piano for his friends’ enjoyment. The guitar played a central part in the development of the waltz during Schubert’s life. In the Austrian Alps, the Styrians, where the waltz was popularized, musicians performed waltzes in ensembles comprised of violins, clarinets, guitar, and bass. Famed waltz composer Joseph Lanner performed his waltzes in ensembles with guitar and violin.

Quartetto, D. 96

Further contact with the guitar and compositions for the instrument came through the quartet Schubert’s father held with his friends.[11] It was for this ensemble that Schubert arranged Matiegka’s Noturno, Op. 21 by rewriting significant portions and adding a cello part to the work originally for flute, viola, and guitar. The original was published in Vienna by Artaria and Company in 1807, seven years before Schubert dated his manuscript “February 27th, 1814.” Hints to the origins of Schubert’s arrangement are found throughout the work, most notably on the title page where Schubert began to write the word “Terzetto,” crossed out this and wrote in his own title “Quartetto.” Schubert did not however make any direct note of Matiegka’s original title Noturno. He indicated, nevertheless that several variations in the final movement would remain the “same as in the printed trio.”

Comparative analysis of guitar’s role in the second Trio with the surrounding movements, suggests Schubert’s true capabilities as a guitarist. In the Trio II Schubert’s original writing for the guitar reverts to the more simple arpeggiated figures and block chords like those found in the Terzetto, D. 80. The reduced texture of the guitar part indicates Schubert perception of its position in the ensemble, and provides solid evidence of Schubert’s narrow, yet capable knowledge of the instrument.

Works for Solo Voice and Guitar: Die Nacht, WoO (c. 1840)

Between 1840 and 1842 Schubert’s friend and colleague, Franz von Schlechta arranged and copied works for his own performance on the guitar. In all there are 99 volumes dedicated to guitar music for solo, duo, and vocal accompaniment. While only a few works are included by famous Viennese composers such as Beethoven, Mozart, and Haydn, Schubert’s works span 39 volumes (51-89) in this project.[12] Die Nacht is one work included in this collection. Upon first glance this manuscript seems to be the only surviving Lied with original guitar accompaniment, but after closer investigation the evidence supporting such claims takes on a more complex form. Most interesting in Schlechta’s copy is that, lying easily on the instrument, the accompaniment seems as if it were originally conceived for the guitar.[13] However, the same Lied appears at the end of the volume transposed to C major. Here, additional text on the title page states that the work was “arranged by J. N. Huber”, a known guitar arranger in Vienna during Schubert’s lifetime.[14] This may refer to the arrangement of a lost piano manuscript or simply to the transposition from the original key. In any case, this Lied’s contribution to the understanding of the guitar’s place as an accompanying instrument is immeasurable.

About the Artists

The musicians featured on this recording include faculty and students from the Florida State University College of Music. Their dedicated efforts help make Florida State University one of the preeminent sources of musical excellence in the United States.

This project was funded in part by a grant from the Theodore Presser Foundation. For further information on the subject of Franz Schubert and the guitar, please refer to Dr. Mattingly’s treatise, “Franz Schubert’s Chamber Music with Guitar: A Study of the Guitar’s Role in Biedermeier Vienna,” available online.

Special thanks to Kris Anderson, Seth Beckman, Larry Gerber, Thomas Heck, Bruce Holzman, Richard Long, John Reed, Leo Welch, and especially the Theodore Presser Foundation.

Cover art reproduced with kind permission from the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Vienna. The graphic art design is by Leanne Koonce.

End Notes:

1 Belangia, Kay Griffin. The Influence of the Guitar and the Biedermeier Culture on Franz Schubert’s Vocal Accompaniments. Dissertation: Master’s Thesis, East Carolina University, 1983, p. 33.

2 Berke, Dietrich. Franz Schubert: Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke. Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1974. p. xxii.

3 Dürr, Walther and Andreas Krause. Schubert-Handbuch. Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1997, p. 278.

4 Mandyczewski, Brahms, et al. Franz Schubert: Complete Works. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel, 1897. Vol. 16.

5 Formerly listed as D. 641 in the Schubert Thematic Catalogue, this work is now referenced as D. 598b. See Brown, Maurice John Edwin with Eric Sams. “Schubert, Franz” (work-list), Grove Music Online ed. L. Macy (Accessed 21 December 2005),

6 Deutsch in Reinhard van Hoorickx, Schubert’s Guitar Quartet, D. 96, Revue belge de Musicologie. Vol. 31 (March-April 1977), p. 122.

7 Flower, Newman. Franz Schubert: The Man and his Circle. New York: Tudor Publishing, 1936, p. 345.

8 Ibid., p. 335.

9 Deutsch, Otto E., and Wakeling, Donald R. Schubert Thematic Catalogue of all His Works. New York: Edwin F. Kalmus, 1950, p. 33.

10 Schneider, Marcel. Franz Schubert. In Selbstzeugnissen und Bilddokumenten, aus: rowahlts Monographien, herausgegeben von Kurt Kusenberg. Hamburg: 1968. Cited in Schult, Vike, p. 31.

11 Kinsky, Georg. Forward to the Published Edition of the Quartet D. 96. New York: C. F. Peters, 1956.

12 Scheit, Karl and Partsch, Erich Wolfgang. Ein unbekanntes SchubertLied in einer Sammlung aus dem Wiener Vormärz. Schubert durch die Brille: Internationales Franz Schubert Institut Mitteilungen, No. 2 (January, 1989), p. 15.

13 Ahrens, Christian. Zur Rezeption der Gitarre in Deutschland im 18. und 19. Jahrhundert. Bach & Schubert: Beiträge zur Musikforschung, Jahrbuch der Bachwoche Dillenburg, (1999): Vol. 33, p. 27

14 Scheit, p. 18